Physical Security Program Best Practices

- Chapter 1: Tutorial & Best Practices

- Chapter 2: Commercial Building Security Systems

- Chapter 3: Physical Security Systems

- Chapter 4: Data Center Physical Security

- Chapter 5: Physical Security Cybersecurity

- Chapter 6: Physical Security Plan

- Chapter 7: Physical Security Controls

- Chapter 8: Retail Security Systems

- Chapter 9: Physical Security Tools

- Chapter 10: Physical Security Program Best Practices

- Chapter 11: Physical Security Policy Best Practices

- Chapter 12: Best Practices for Physical Security and Cybersecurity

- Chapter 13: Best Practices for Corporate Physical Security

- Chapter 14: Physical Security Best Practices

- Chapter 15: How physical security powers

For modern organizations, physical security must evolve beyond the decades-old philosophy of simply “guns, guards, and gates.” The threat landscape in the 21st century looks nothing like it did previously: Today’s threats are more common, more widespread, and have the potential to be much more disruptive to companies and their employees, operations, and clients.

It is against this new backdrop that physical security practitioners must assess their programs. The new reality requires a comprehensive framework of governance, technology, and operations that combines both proactive assessment and response-based management to mitigate physical threats.

This article explores the three major components of a modern, technology-converged physical security program and recommends best practices for security governance, technology, and operations to protect a business.

Summary of best practices for a physical security program

| Best Practice | Description |

|---|---|

| Security Governance | |

| Develop and implement a governance program | Create clear policies, standards, and playbooks as the foundation of a physical security program; involve stakeholders such as IT, legal, and facilities. |

| Create a security personnel roadmap | Develop a strategic plan for the selection, hiring, and training of security personnel. |

| Future-proof with converged security | Adapt governance by aligning physical security with cybersecurity programs; prepare for risks and opportunities as responsibilities shift from facilities to IT. |

| Security Technology | |

| Integrate technologies for layered defense | Combine perimeter defenses (e.g., bollards, fencing, and IDS) with access control, CCTV, and visitor management to form a unified monitoring approach. |

| Manage device lifecycles effectively | Track end of service (EOS) and end of life (EOL) for security devices; apply predictive analysis for maintenance to minimize downtime and improve resilience. |

| Security Operations | |

| Enable operators as technical force multipliers | Equip GSOC operators and security personnel with better tools to handle both operational and more technically complex issues. |

| Enhance ROI and reduce costs | Minimize costly device outages with manned security personnel by using efficient monitoring and streamlined workflows. |

| Continuously train and improve operations | Provide ongoing training and audits to ensure that employees adapt to evolving technologies, threats, and organizational requirements. |

-

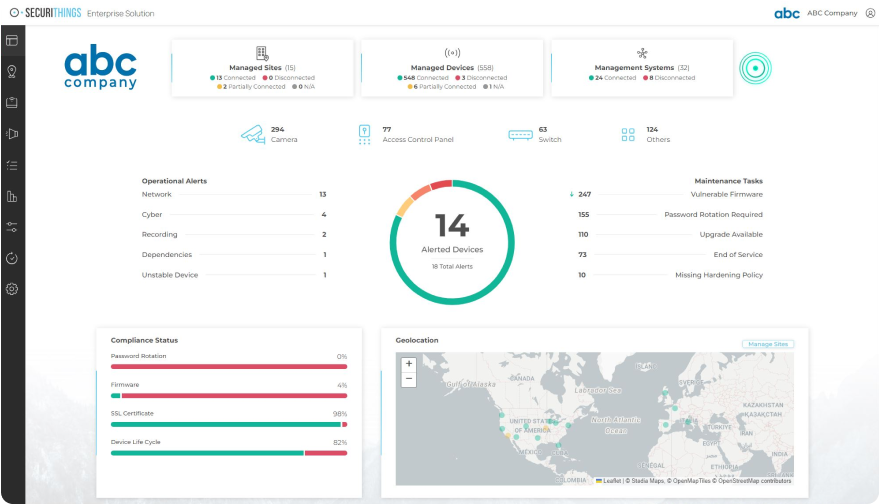

Monitor the health of physical security devices and receive alerts in real-time

-

Automate firmware upgrades, password rotations & certificate management

-

Generate ad hoc and scheduled compliance reports

Security governance

Develop and implement a governance program

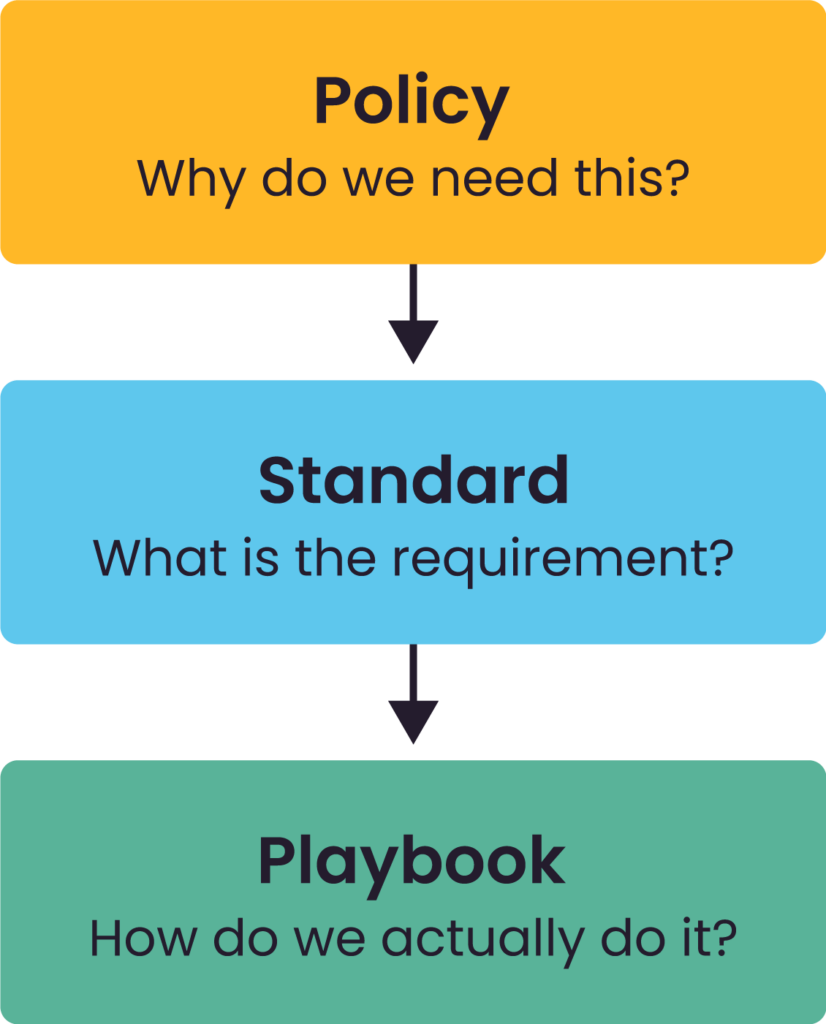

The key difference between policies, standards, and playbooks.

Governance should be considered the foundation of any effective security program. Policies, standards, and playbooks should be seen not just as something to write and put on the shelf to be forgotten. Instead, look at them as the lifeblood of the organization: items that should be constantly reviewed, refreshed, and updated.

A strong governance program includes the following elements:

- Security policy: This document should define why security is needed, the organizational objectives and business risks, and the high-level roles/responsibilities of different functions in achieving this. An effective security policy should be supported by a C-suite executive sponsor and should include input and approval from various stakeholders, including IT/cybersecurity, facilities/workplace, legal, and HR.

- Security standard: This set of documents should define the different requirements to achieve the objective of the security policy. This can include documents that outline the type of fencing to be used, what type of physical access control system (PACS) will be installed, and types and models of IP CCTV to be used on site. An effective set of security standards should also outline how monitoring and compliance with these sets of guidelines will be achieved; for example, if a company is using an older style analog camera system, what is the process for updating to a more secure IP camera system?

- Security playbooks: This set of documents defines how the work is actually done and can include playbooks that outline how visitors are to be checked in, how to respond to security incidents, and how to triage operational failures (e.g., if a card reader is not functioning, what are the next steps?) An effective set of security playbooks will incorporate input from line staff and users to ensure that the processes that are being written are actually achievable and being done in a uniform/consistent way.

Without an effective governance program, teams and technology often operate in silos and can fail to deliver an effective business-first program.

Create a security personnel roadmap

An effective physical security program should include a strategic roadmap that assesses and determines personnel needs. This plan should outline at least some of the following: security roles, number/type of personnel needed, and training/qualification requirements.

Determine the best security model for the organization

In a 2024 survey of CSOs, approximately 40% said that they outsource at least some part of their security functions. This trend is unlikely to change because companies are increasingly outsourcing not only lower-level personnel but even entire departments. With functions that are seen as easier to outsource, security practitioners should ensure they have the following:

- A solid elevator pitch: This should be a 2-3-minute quick pitch to demonstrate to an executive and/or department head the value of the security programs.

- A current and future headcount plan: This should include an effective understanding of the roles/responsibilities of the security team, what their priorities are, and longer-term needs that the department might have.

Recruit and select the right personnel for a corporate security program

Security programs often take the approach that hiring former law enforcement or military personnel will automatically give their program a boost. While there is inherent value in hiring from these types of backgrounds—particularly for investigative and/or technical roles—it is important to also think about cultural fit, aptitude, and business mindset.

When thinking about the selection process for security roles, here are some questions to consider:

- Is this a role that requires specialized background or experience, or can the skills be trained?

- Does the candidate have relevant background and/or transferable skills for the role?

- Does this role require a business and/or corporate mindset to be effective?

Develop and maintain succession plans

A business continuity concept that is often overlooked in most security programs is succession planning. Security practitioners should continuously ensure that their personnel are cross-trained and that there are mechanisms in place to handle departures. For example, this could mean developing a robust training program and the necessary KPIs/SLAs with the security vendor if there were mass call-offs due to illness or a natural disaster. This ensures that the security program has a robust personnel plan in place to continue operating even if under diminished capacity.

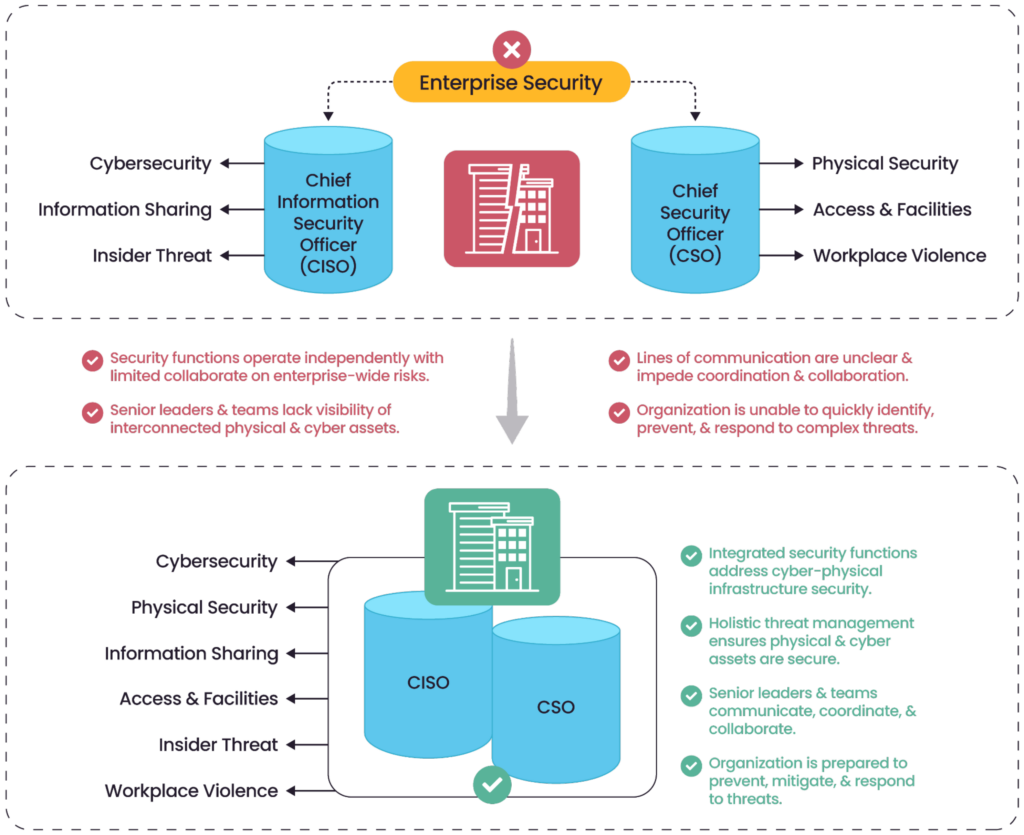

Future-proof with converged security

Historically, physical security and cybersecurity interacted and intersected with each other, but traditional corporate structures, embedded organizational beliefs, or a lack of understanding have kept them siloed. Threats are no longer exclusive to a domain; take, for example, a terminated employee who piggybacks into a building and then inserts a malicious USB into the company server.

Here are some specific approaches to consider:

- Create an enterprise security working group: Security professionals should seek executive sponsorship and support to create a working group that includes selected key personnel from physical, cybersecurity, and other relevant stakeholders. This should start with a clear charter and mandate so that neither side feels like they are being usurped by their peers. The initial aim should be to broaden collaboration and eventually become a center of excellence (COE) where ideas, thoughts, and projects—for example, partnering on security technology—can originate that support both the physical and cybersecurity needs of the organization. A longer-term objective for the working group should be a forum where functional departments that play a role in enterprise security (like HR, legal, and compliance) can have a seat at the table.

- Integrate incident management: An insider threat incident highlights the need for enterprise security, where threats can be triaged, analyzed, and responded to holistically. Physical and cybersecurity professionals should develop a framework for how cross-domain incidents will be managed. This should include specific guidelines on items like who “owns” the incident, agreements on notification processes/workflows, and who is responsible for case management. An important but often overlooked step is the need for a standardized case number reference that is used across the organization for incidents.

- Implement a job rotation initiative: A job rotation initiative is a key step that can help personnel from both programs better understand their counterparts and develop a shared mutual commitment to protect their organization. This program should initially be for middle managers who have the most ability to influence both up and down in their respective departments, with the wider goal to be that every employee does this at some stage, from analysts to even the CSO/CISO.

A bifurcated physical and cybersecurity program compared to converged security functions (source)

Security technology

Integrate technologies for layered defense

Traditional static defenses—like gates, fencing, or bollards combined with more intelligent interior defenses like card readers, motion detectors, and CCTV, and the final deterrent of a security officer—are becoming increasingly outdated as a deterrent.

Here are some specific steps to look at:

- Add smart static defense: The Internet of Things (IOT) is increasingly becoming embedded in static perimeter defenses like bollards. A smart perimeter defense that integrates new technology can help reduce the burden on security teams by automating manual tasks. By effectively leveraging IOT physical security, practitioners can gain better situational awareness of their sites while minimizing the manual outputs. For example, smart bollards with CCTVs, sensors, and AI-configured analytics are rapidly reducing the need for human intervention.

- Upgrade to “friendly” physical access controls: As business enablers, security practitioners should constantly strive to strike a balance between security and ease of use. A move toward smart access control that allows mobile credentials means users have more freedom and flexibility for access control management. Physical access control systems should integrate security, design, and usability to better meet organizational needs.

- Develop a unified approach for managing multiple technologies: With multiple new technologies available, an often overlooked aspect is how to correctly manage all the various systems together in a coherent and effective form. Physical security management should shift away from closed/proprietary device management systems and look for more integrated systems that can allow device management, dashboarding, and aggregation to ensure that their systems are working correctly and effectively to protect their people.

A centralized device management system to monitor all security devices (source)

Manage device lifecycles effectively

A report published by a leading technology company’s global operation center estimates that they monitor approximately 10,000+ card readers, 15,000+ cameras, 900+ video recorders, and several hundred fire panels. While this is a more extreme example of what companies face, it underscores the highly cumbersome and increasingly expensive nature of device cycle management.

Here are a couple of important ways to achieve success in this area.

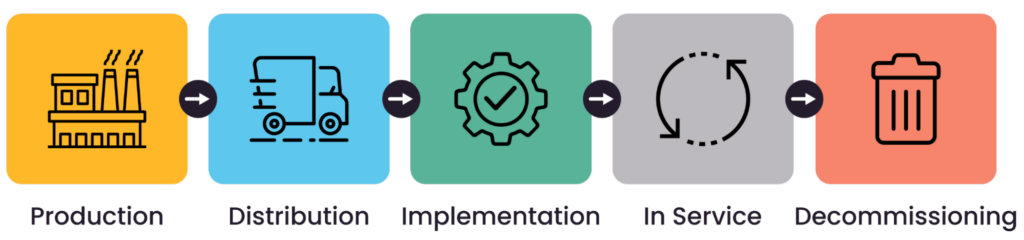

Manage end of service (EOS) and end of life (EOL) across all devices

Companies continue to rely on outdated forecasting models (for example, a 5-7 year security technology upgrade cycle) or oversized input from security integrators on the life cycle management. Since most security teams do not always have the technical expertise, bandwidth, or physical reach to inspect devices, this creates a technology gap. Physical security practitioners should:

- Use technical solutions that can be integrated with a wide variety of different platforms/technologies.

- Foster true partnerships with security integrators to ensure that the advice/expertise provided is fit for purpose.

- Regularly assess and test new solutions on site to familiarize themselves with different technologies and their possible use cases.

- Benchmark with like-sized/risk-based peers to assess new methods and security technologies.

- Ensure that continuity plans are updated in the event of large-scale device outages.

The device life cycle from production to decommissioning (source)

Implement predictive device forecasting

As an inherent cost center, security teams must continue to drive innovative methods to be seen as cost-conscious. Through effective predictive forecasting, security teams can pre-plan upgrades to minimize issues like geopolitical changes or currency fluctuations that hinder operational control and drive costs.

Security teams can implement effective forecasting through some of the following change controls:

- Device management systems: Implement an integrated software system responsible for device management.

- Stakeholder engagement: Conduct regular check-ins, particularly with sites that do not have dedicated security personnel, to ensure that security technology is maintained and working optimally.

- Use informed decision-making: Consider operational needs when conducting maintenance/upgrades. For example, instead of upgrading security systems in multiple countries such as Brazil, Chile, Spain, and France, consider a regional model that upgrades all technologies in LATAM or Europe.

Security operations

Enable operators as technical force multipliers

A global security operations center (GSOC) is the 24/7/365 nerve center for all physical security alerts, activities, incidents, cases, and crises. Operators, who are often former security officers, are constantly bombarded with information, creating a high level of information overload.

Start by empowering GSOC operators with more informed data. When security systems fail, GSOC operators are often the first line of defense, yet they are often not adequately trained to understand and explain the issue. This is more acute with physical access control systems that have clunky interfaces, have too little or too much information on screen, or require specialized time-intensive training to understand.

Specifically:

- Implement a device management system allowing operators to determine if the device outage could be attributed to firmware, hardware, or physical damage.

- Consider hiding unnecessary information on the PACS to minimize information overload.

- Provide effective call scripting and playbooks for GSOC operators to better relay information.

Develop a good relationship between the GSOC and the security integrator. An effective GSOC should be empowered to engage directly with the security integrator. This should include written service level agreements (SLAs) for the vendor on GSOC call-outs and training for GSOC on what issues should be escalated to the security integrator directly versus the in-house security team.

Enhance ROI and reduce costs

All physical security teams face a constant challenge in how to justify their budgets. It’s impossible to prove a negative: When a security team prevents a significant incident, there is often no metric or data that can be used to justify the investment that led to this result or how much money was saved.

Here are some important ROI-related actions:

- Implement key performance indicators (KPIs) for technology failures and their associated guard costs: When there is a security device outage, a security officer is often sent as a deterrent; security practitioners should strive to track device outage metrics and these resulting costs. For example, if an exterior card reader door is failing regularly, it may be more cost-effective for the facilities team to replace the door than for security to constantly send personnel to monitor access while the door is repaired.

- Integrate security patrols with manual device health and monitoring checks: Security officers should use patrols not only to observe and report but also to test and ensure that security technology is functioning correctly. Patrol playbooks should be updated regularly, and security officers should be trained on how to perform functional device checks as part of their checklist requirements.

- Regularly update and assess security integrator KPIs/SLAs: An effective physical security program should regularly assess the capability of its security integrators. Start-up/scale-up companies often use a vendor and continue this relationship even though the vendor might not be adequately meeting their needs as the company grows. This assessment should include both informal catchups—to discuss the business relationships—and formal KPI/SLA meetings to assess vendor management and technology performance.

Continuously train and improve operations

Security teams must not rest on their laurels. They need to constantly strive to enhance their performance, keep abreast of new/upcoming threats, and seek innovative ways to protect employees, assets, and operations.

In-house security teams should partner with their vendors to develop and devise a security training program that fits the organization’s requirements. These programs should be enhanced by incident/activity metrics to simulate the most likely threats faced, and they should be multi-modal, including scenario-based training, table-top exercises, or refresher training. For example, if security officers deal with a lot of transient scenarios, training on de-escalation should be required. If they deal with a lot of card reader outages, refresher training should be provided on preventive maintenance/access management techniques.

Security teams should also continue to drive technical and/or creative innovations to enhance effectiveness and reduce manual processes. This can include shifting away from paper-based playbooks to online playbooks where information is indexed, searchable, and archivable. It may also mean creating a “social media presence” to engage with employees; this can include things like a place for security announcements, an online reporting portal, and possibly customer satisfaction scores like voice of the customer or net promoter scores.

Last thoughts

An effective physical security program is about more than just its component policies, technology, and people. It must be adaptable, scalable, and flexible. Good governance practices, integrating “smarter” security technology, having security personnel become more important to operations—each of these elements must work together.

To mitigate risk, physical security practitioners must ensure that their programs have the right governance (business/risk-focused to their organizations), the right technology (deployed, monitored, and maintained for their threat landscape), and the right personnel (who are trained with the right equipment).